The farming days when size really did matter...

We tend to view 19th-century paintings of massive cows and oversize pigs as rather naive artworks now, but as Alison Gifford explains, they were accurate depictions from the early days of intensive farming.

Back in February the traditional mart took place in King’s Lynn for the 483th time, and thanks to the charter granted by Henry VIII the fun-filled event has seen everything from the town’s first experience of ‘moving pictures’ (thanks to Randall Williams’ cinematograph booth in 1897) to Frederick Savage’s innovative fairground rides during the later half of the 19th century.

Visitors to the event were in for a real treat in 1826, when a poster advertised the appearance of a “surprising large ox” - which was described as “seventeen hands high” (around 5ft 7inches), an improbable 18ft in length, and weighed an equally jaw-dropping 150 stone - which is almost 953kg. It was, as they say, a whopper.

The ox in question had been bred by Wiggenhall St Germans farmer Thomas Fuller, who put it on show at the Crown and Mitre pub on Ferry Street in King’s Lynn - although whether the animal was displayed inside or out isn’t specified. Gentlemen and “working people” presumably knew their place and how much to pay to see this awe-inspiring spectacle - because the charges were sixpence for the former and threepence for the latter.

In the early 19th century, fat cows, massive pigs and obese sheep were prized as proof of their owners’ success in breeding for size and weight - and gentleman farmers used selective breeding to create quick-growing, heavy livestock. At the same time new intensive farming and feeding practices also produced larger animals - and rich farmers (called ‘improvers’ after their efforts to make existing animal breeds bigger and better than ever) avidly read the latest research in the newly-published farming magazines.

They fed their cows oil cakes and turnips for a final fattening-up before slaughter, and even Prince Albert became an ‘improver’, showing off his prize pigs and cattle. The enormous animals were exhibited all over the country by their proud owners to an astonished public.

This actually created a class of animal celebrities, such as the Durham Ox - who was born in March 1796 on a farm in Darlington.

Even today there are many public houses named after him and his larger-than-life image was even used as a pattern for dinner plates.

Even more famous was the Craven Heifer, who was bred by the Reverend William Carr in 1807. At her prime (around 1811), she stood almost 7ft tall at the shoulder and weighed an incredible 312 stone (1,981kg) - and the huge cow became a genuine superstar, touring the country and attracting admiring crowds at various agricultural shows.

These exceptional animals could be sold for a considerable amount of money (the Craven Heifer was sold for the equivalent of some £13,000) but only elite breeders had the time and wealth to develop such prizes. Many aristocrats and gentlemen owned large agricultural estates, and breeding was considered a high-class pastime.

Surprisingly, until agriculture became established as a semi-scientific business in the late 18th century, there weren’t any named breeds, just various types of animal that had been adapted over time to their working environment - big horses for ploughing, small ones for the coal pits, and long-haired cattle who’d adapted to the colder climates of Scotland. Until then, little or no attempt was made to manipulate the breeding of livestock for better (or more) meat, fat or wool.

One local landowner who took the science of stock improvement very seriously was Thomas Coke at Holkham, a gifted agriculturalist and skilled self-publicist who transformed the surrounding estate and became famous as a cattle breeder, grass and turnip pioneer, and agricultural reformer.

Britain’s population during the Industrial Revolution increased significantly, so having a secure food supply of fat animals was imperative - and ‘improvement’ progressed quickly. Between 1710 and 1795, the average weight of the average British cow increased by a third.

Gentlemen farmers used altruism to justify their self-promotion and plain showing-off with their mega-animals - if they could breed larger, fatter cows (they said) then poorer farmers could eventually own them. With more meat to sell, rural communities would be more financially stable. The health and wealth of the whole country would improve. Or so went the argument.

One of the experts employed when the new Board of Agriculture was established in 1793 was Charles Vancouver (two years older than his famous explorer brother George), who was engaged to write reports on the state of agriculture in a number of English counties and was described in July 1795 as “a sensible well-informed man.”

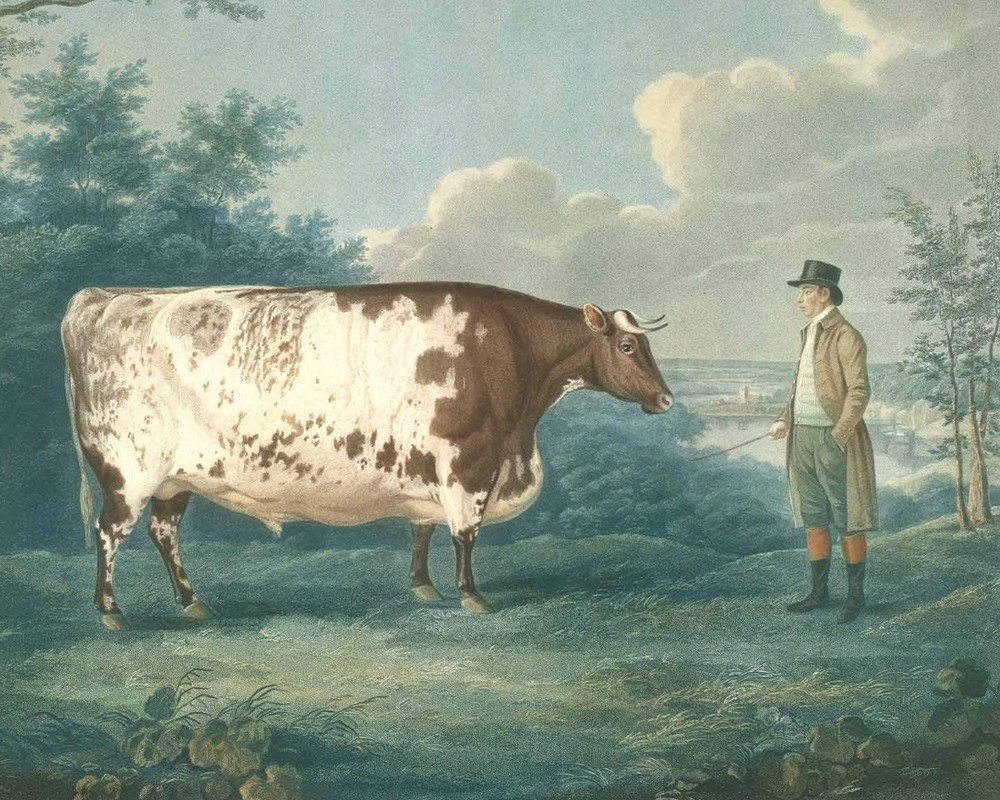

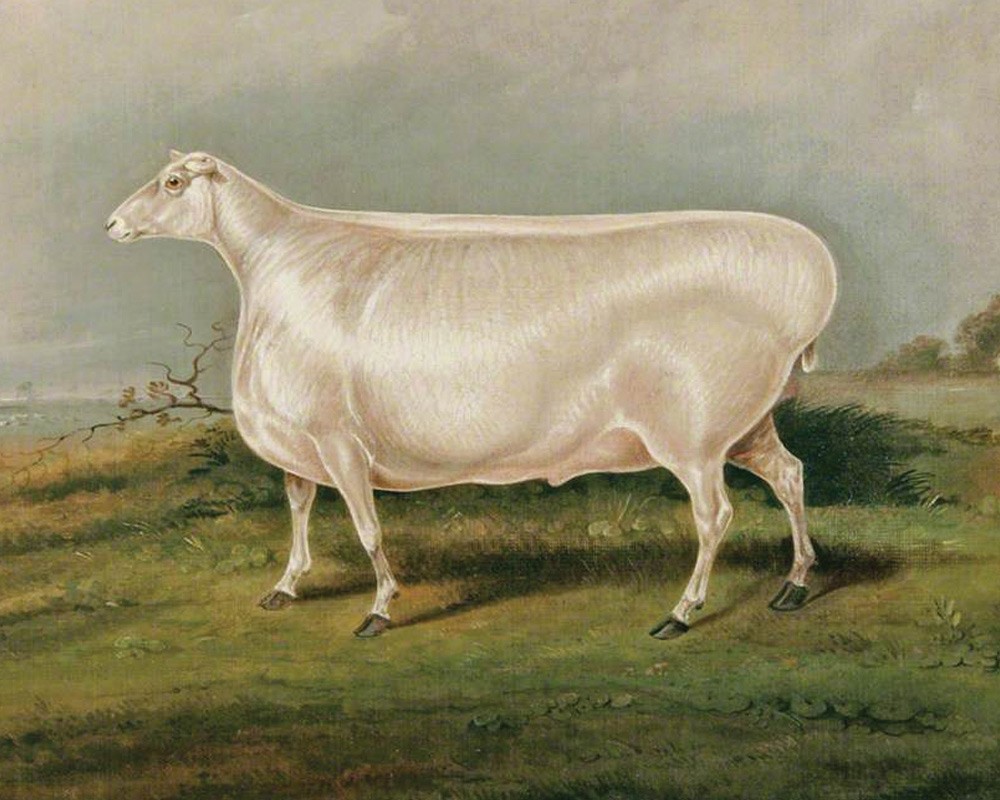

Painting farm livestock reached its peak in the early nineteenth century, when prize-winning beasts were painted as trophies for their proud owners. Horses had always been depicted for their grace and elegance but for farm animals, corpulence was key. In the paintings, the cows, sheep, and pigs are massive, yet oddly supported by only four spindly legs. Sometimes, their owner is featured as well, admiring his creation. The resulting images were part advertisement, part spectacle.

Local father and son artists, James and John Scraggs (who lived in Friar Street, King’s Lynn) painted and exhibited local prize livestock pictures such as the ‘Enormous Sheep’ from Wimbotsham displayed in Lynn Museum and the ‘Heifer in a Norfolk Landscape’ exhibited by the Norfolk and Norwich Society of Artists in 1816.

Commissioned paintings and commercial prints often came with information about the animal’s measurements and the owner’s breeding efforts. How true to life the pictures were is questionable as body parts were often exaggerated to emphasize the idealized animal shape. For pigs, the ideal was a football shape, whereas cattle should be as square as possible - and sheep were best when oblong. All the same, some of the portraits which look so improbable were drawn to scale and do agree with the dimensions so carefully recorded on the prints.

The animals in these pictures may look ludicrous to modern eyes (and raise a number of increasingly important ethical questions) but to the gentlemen farmers of Norfolk 200 years ago, they were a visible source of pride and joy.

And an extremely big one at that.