Wisbech & Fenland Museum

From the very first, museums were intended as a way of bringing a weird and a wonderful world closer to home. It’s a tradition admirably continued by the Wisbech and Fenland Museum

The Wisbech and Fenland Museum is one of the oldest purpose-built museums in the whole country, and thanks to its fully-preserved Victorian interior (along with the original display cases) it repays visitors with a very real sense of stepping back in time. It looks Victorian and it feels Victorian, with every cabinet demonstrating the period’s love of combining scientific classification with collecting the weird and the wonderful.

Whether it’s the giant eel caught in the River Nene, the ornately-framed mummified hand of an Ancient Egyptian, the recreation of Mrs Pooley’s shop and post office in Elm, the stupendous collection of Staffordshire figures or the 1888 model of Sutton Bridge, there’s something in this hugely atmospheric museum that will appeal to everyone.

Back in July 1835, and under the guiding force of Algernon Peckover, 31 gentlemen from the upper ranks of Wisbech society gathered in support of a museum being made available to the people of the town.

The committee found a suitable home (a detached portion of George Snarey’s house in the Old Market) and spent £47 on wall cabinets, table cases and drawers for the mineral and insect collections, opening the museum for three hours on Fridays. The entrance fee was one shilling per person.

It was an immediate success, and as the Museum grew in popularity and more collections were donated the rooms soon became overcrowded.

The Trustees (and the Museum is still an independent charitable trust today) realised a purpose-built museum was required and started looking for a permanent location.

On 3rd January 1846 the Wisbech Advertiser reported that “the Trustees of the Wisbech Museum have joined with the Wisbech Literary Society in the purchase of a piece of ground adjoining the churchyard and opposite the Castle Lodge” – it cost them the grand sum of £2,500.

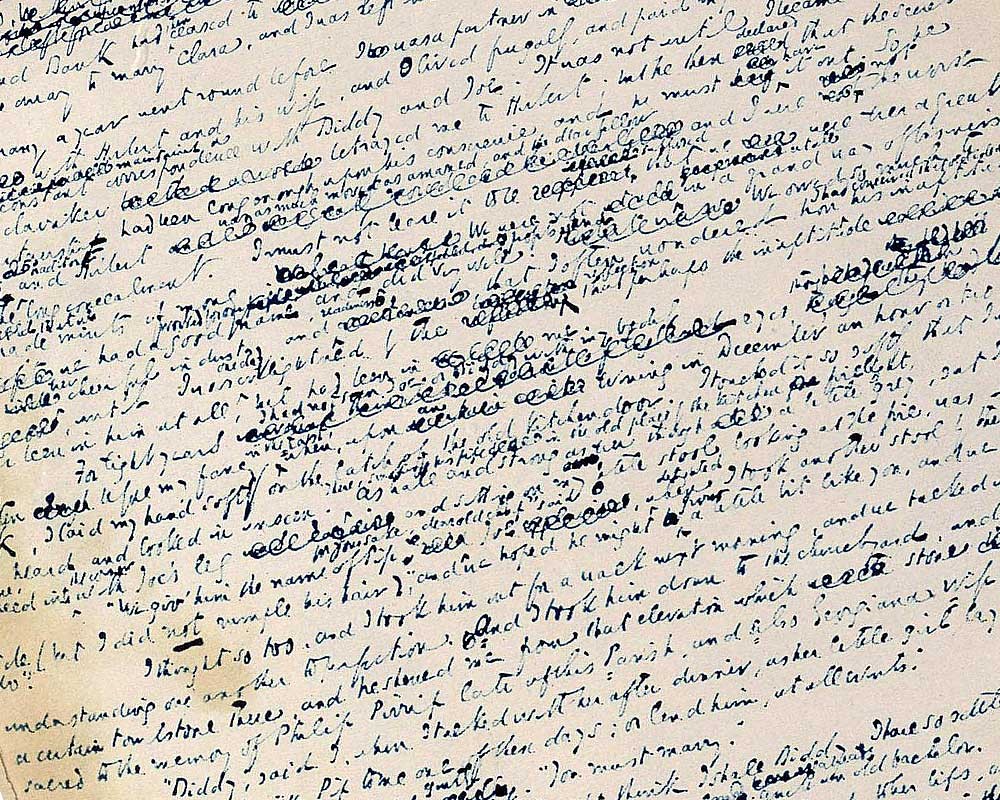

Designed by JC Buckler, the museum incorporated two wings linked by a common entrance hall and a lecture room – the larger wing housed the Museum, while the smaller was taken by the Literary Society for their library (which has been the home of Charles Dickens’ original manuscript of Great Expectations since 1868).

The Wisbech and Fenland Museum opened its doors on 27th July 1847, and for almost 170 years it has continued to entertain and educate people of all ages from all walks of life.

Picking highlights from the collections is an almost impossible task, but one of the most unusual (and fascinating) displays is the Cabinet of Curiosities. Inspired by the very earliest ‘museums’ of the 16th and 17th centuries (they largely died out when museum collections were broken up and displayed according to stricter standards of scientific classification), it’s a wonderful assembly of interesting and peculiar items.

The William Smith Collection of Staffordshire figures (more than 80 pieces were donated to the Museum by his daughter in 1900-01) presents an eclectic cast of personalities from Cleopatra to Benjamin Franklin, and shouldn’t be missed. William Smith was a chemist (his shop was at the junction of High Street and Bridge Street) and in later life was widely regarded as an authority on the subject of fine art and supported many of the exhibitions held in Wisbech.

Naturally, there’s a marvellous tribute to the life and work of local anti-slavery campaigner Thomas Clarkson. To gather evidence against the slave trade, he travelled 35,000 miles (1½ times around the world!) and interviewed some 20,000 sailors, collecting items demonstrating the cruelty of the trade in a specially-made chest. An important part of his public meetings, Clarkson’s Chest is an interesting example of an early visual aid and travelling museum – in addition to its sheer historical significance.

Another quite remarkable exhibit at the Museum is the collection of Victorian miniature models of dinosaurs and other ancient animals. Made from lead and plaster-of-Paris, they’re almost certainly replicas of the life-sized reconstructions installed at Crystal Palace in 1852 (and which can still be seen today) – but the actual identity of the model maker and how they ended up in the Museum remains shrouded in mystery.

Mystery, fascination, and wonder – the Wisbech and Fenland Museum is packed with all three. It’s unmissable.